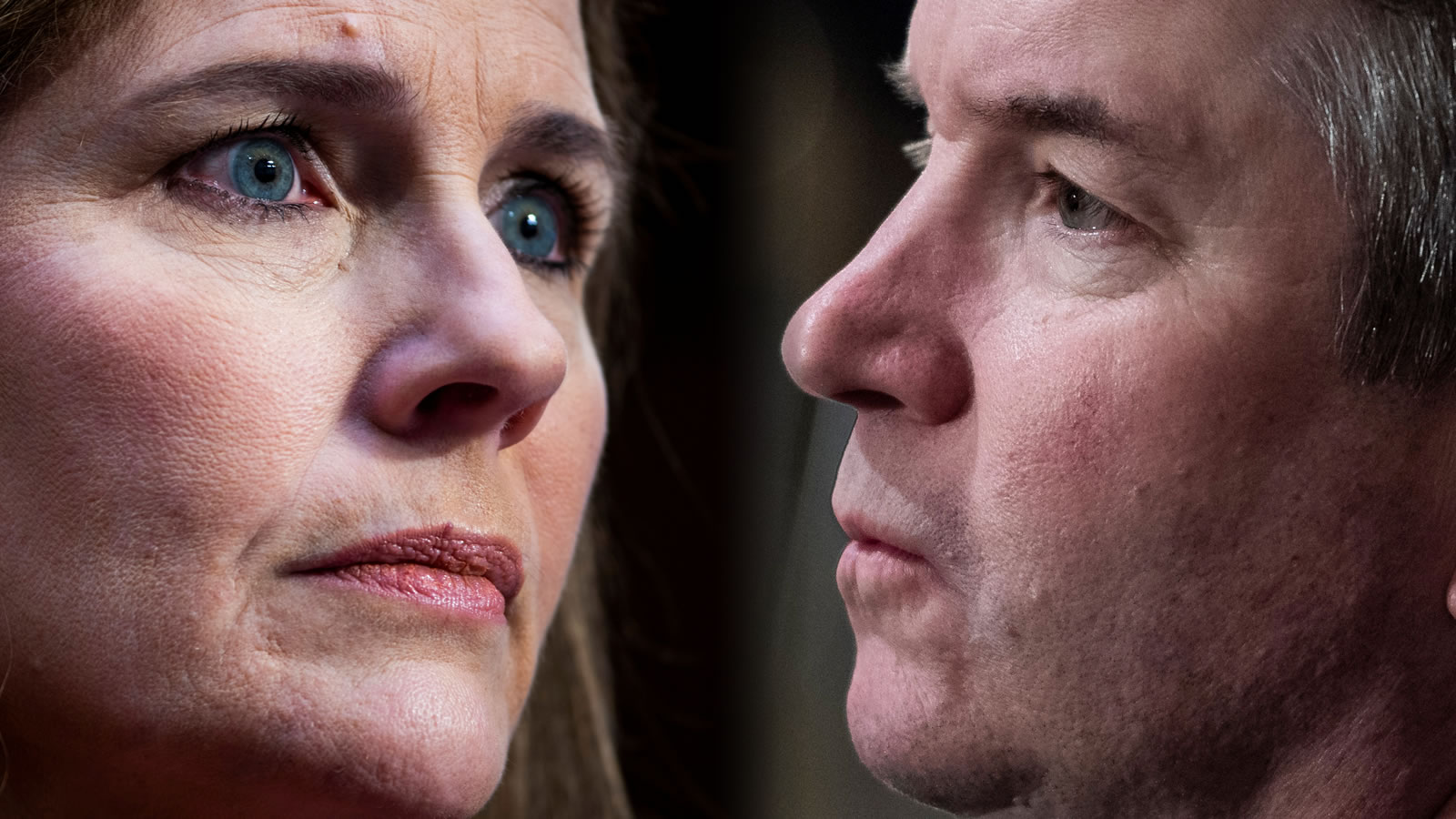

Late Friday, Justices Amy Coney Barrett and Brett Kavanaugh joined Chief Justice John Roberts and the Supreme Court's three progressives in denying a preliminary injunction to a group of medical professionals who sought to be exempted from Maine's vaccine mandate because of their religious convictions.

Justice Neil Gorsuch filed a compelling dissent in the case, John Does 1-3 v. Mills, joined by his fellow conservative justices, Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito. The dissenters stressed that, besides being likely to win on the merits, the religious objectors were merely asking to maintain the status quo – to keep their jobs despite being unvaccinated — while the Court decided whether to grant a full review of their case. In turning them down, Barrett and Kavanaugh dodged the weighty civil-rights issues, seeing the case, instead, as an opportunity to gripe about the Court's emergency docket.

Maine now requires certain health-care workers to be vaccinated or face the loss of their jobs and medical practices. Unlike many such mandates, Maine's does not provide an exemption for religious objectors. The plaintiffs are medical professionals who object to the vaccine, and thus the mandate, based on their Christian faith. Specifically, because fetal tissue from terminated pregnancies was used in developing the approved vaccines, the plaintiffs see immunization as an implicit endorsement of abortion, in violation of their religious beliefs. The sincerity of those beliefs is not in dispute.

The plaintiffs made an emergency application for a preliminary injunction. In his dissent from the 6–3 majority's refusal to grant that application, Gorsuch explained that the main issue on such an injunction request is whether the applicants are likely to succeed on the merits and, if so, whether they would suffer irreparable harm in the absence of an injunction. Gorsuch proceeded to make a strong case that the claimants would prevail on both issues.

Religious liberty is fundamental, expressly protected by the First Amendment. Under currently controlling precedent (which, as I've previously detailed, is disputed), a law that impinges on religion may survive if it is both neutral (i.e., not hostile to religion) and generally applicable (i.e., imposed on everyone equally). Maine's vaccine mandate does not meet this standard because it provides for individualized exemptions. Though medical professionals are not excused from compliance based on their religious beliefs, they needn't comply if they get a note from a health-care provider claiming that, in their cases, immunization "may be" medically inadvisable.

As Gorsuch elaborates, this medical exemption is remarkably lax. There is no requirement that the note explain why the health-care provider believes vaccination would entail medical risk; nor is there any limitation on what qualifies as a valid "medical" concern. As Gorsuch tartly observes, "It seems Maine will respect even mere trepidation over vaccination as sufficient, but only so long as it is phrased in medical and not religious terms." (Emphasis in original.)

Even if law fails to qualify as neutral and generally applicable, it can still survive a First Amendment challenge if it satisfies the Court's "strict scrutiny" tier of review — the most demanding for state action to meet. Generally, strict scrutiny requires a state to show that (a) its law furthers a compelling government interest, and (b) the conditions imposed by the law are the least restrictive means of furthering that interest.

The dissenters were willing to stipulate that Maine has a compelling interest in halting the spread of COVID-19, but only for argument's sake. Gorsuch, Thomas, and Alito point out that much has changed for the better since the Court presumed a compelling state interest nearly a year ago (in Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Brooklyn v. Cuomo), there now being not one but three approved vaccines, as well as greatly improved therapeutics, with more on the way. The dissenters are skeptical about the specter of "indefinite states of emergencies," by which state power imperils civil liberties regardless of changed circumstances.

On the second test, Gorsuch demonstrated that Maine appears to fall woefully short of meeting its burden. Many states that impose a comparable mandate provide an exemption based on religious objections. The state has already exceeded the 90 percent level of vaccination compliance at designated health-care facilities that it originally claimed was necessary; even putting aside that the state never backed up this goal with evidence, forcing religious objectors to be vaccinated would not help if the goal already has been achieved. Maine, moreover, allows unvaccinated workers who have been exempted on claimed medical grounds to take other precautions, such as protective gear and regular testing, in lieu of being immunized. Clearly, there is no reason that these same alternative measures would be any less effective for workers whose exemptions were based on religious scruples instead.

Ergo, Gorsuch aptly concludes, "Maine's decision to deny a religious exemption in these circumstances doesn't just fail the least restrictive means test, it borders on the irrational."

Moving on to other injunction factors (besides the plaintiffs' likelihood of success on the merits), the dissenters pointed out that the denial of religious liberty amounts to irreparable harm under the Court's precedents — quite apart from the fact that the medical workers are also losing their livelihoods. By contrast, the public interest would not be harmed by granting religion-based exemptions, any more than it is harmed by the health-related exemptions that the state provides.

Therefore, Justices Gorsuch, Thomas, and Alito saw no justification for refusing to grant a temporary injunction. After all, that would merely maintain the status quo until the Court could decide whether to grant review (known as certiorari) and fully consider the case on the merits.

As for the six-justice majority, it is to be expected that the Court's three progressives (Justices Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan) would elevate state authority over religious liberty. Nor is it surprising that Chief Justice Roberts would subordinate religious liberty to a draconian state mandate. He has a track record in COVID cases of deferring to the judgment of elected officials — no matter how arbitrary that judgment or how fundamental the rights at stake — on the rationale that they, unlike politically unaccountable judges, answer to the voters and have more institutional competence. (See, e.g., his dissent in Cuomo and his upholding of California's restrictions on attendance at religious services in South Bay United Pentecostal Church v. Newsom.)

What is stunning, and will be troubling for conservatives, is the decision by Justices Barrett and Kavanaugh to side with the progressives and turn a blind eye to a state government's suppression of a fundamental freedom that the Constitution is supposed to protect. And equally troubling: the thin gruel they offer as a rationale.

Barrett filed a one-paragraph opinion, joined by Kavanaugh, concurring in the Court's refusal to grant injunctive relief. She explained that she "understands" the weighing of an injunction applicant's likelihood of success on the merits to include "a discretionary judgment about whether the Court should grant review in the case." Discretion in this context means the justices' power to choose to ignore a claim that should be heard, rationalizing that to entertain it could potentially undermine the Court's institutional protocols.

Barrett and Kavanaugh have apparently been seized by anxiety over potential abuse of the Court's so-called emergency docket — a hobby horse among legal academics, particularly now that (a) the Court has a conservative majority, and (b) critics of progressive federal and state administrations are turning to the courts for relief from sundry mandates and decrees.

The emergency docket entails cases that arise in exigent circumstances and must be addressed expeditiously, often by injunction applications, on schedules far tighter than what might generously be described as the Court's customary pace of a hobbled snail. Barrett frets that when the Court takes the "extraordinary" step of entertaining such a case, the justices are put to the unwelcome burden of providing a "merits preview" — a forecast of how the case is likely to be decided if fully reviewed. This is said to be less than optimal because the Court must proceed "on a short fuse without benefit of full briefing and oral argument," when, if they'd had more time to think it through, the justices might not grant review of the case at all.

Cue the violins.

Justice Barrett's temporizing is overwrought. The Court should only grant preliminary relief — which, again, simply freezes a matter in place, but doesn't decide it with finality — if (a) the moving party plainly appears likely to win on the merits, (b) the failure to act would truly cause irreparable harm (e.g., there is no irreparable harm if money damages would eventually make the harmed party whole), and (c) there is not some consequential public interest that an injunction would undermine. That is a very small universe of cases, especially for a tribunal that, on a yearly basis, is not exactly overtaxed. (Last term, the justices issued opinions in just 67 cases out of the approximately 8,000 in which review was sought, continuing the Roberts Court trend of historically low output; in the early 1980s, by comparison, the Court typically decided over 150 cases per term.)

Furthermore, who cares if the Court has to give a merits preview? It is a fact of life that emergency circumstances occasionally arise, forcing us mere mortals to do the best we can, ruefully realizing we could do better if only there were time for calm deliberation. Why should the Supreme Court, the last bastion for safeguarding our fundamental rights, be spared that burden? If it turns out that, upon further consideration of a fully developed record, the justices would not have taken the emergency case in the first place, the "merits preview" does no harm. To the extent it has precedential value, it is understood to be a preliminary decision based on an incomplete factual record.

Most significantly, even if their reservations had persuasive force, Barrett and Kavanaugh are prioritizing the Court's airy model for conducting appellate litigation over its principal duty to defend the fundamental rights of Americans against government overreach.

At issue here is a flesh-and-blood dispute, not an abstraction. Medical professionals are being stripped of their religious freedom and their jobs because of a state mandate that capriciously discriminates against them. Yet rather than take action, Barrett and Kavanaugh basically say: Let's just wait a year or three, so we can have an exacting record and full briefing. And mind you, granting a preliminary injunction would not deprive the justices of their coveted full briefing; it would just mean that the unvaccinated medical professionals got to keep their jobs until the Court finally decided to either deny full review (in which case the injunction would lapse) or grant review and then rule on the merits.

Presumably Justices Barrett and Kavanaugh appreciate that when they exercise their "discretionary judgment" to duck a case, it doesn't mean the case goes unresolved. There is still a winner and a loser. Here, overbearing government prevailed, and the loser was the Constitution.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment