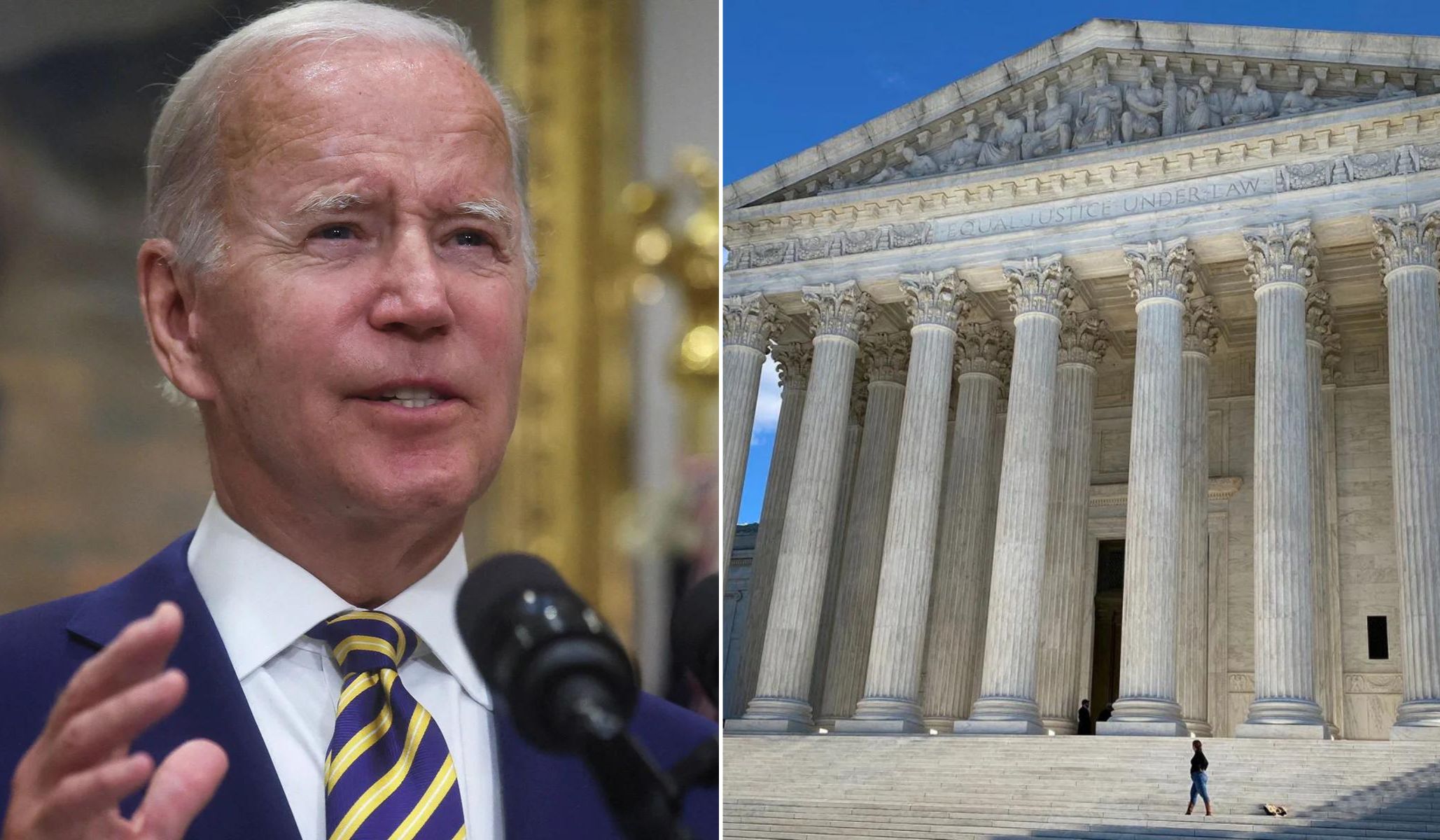

Breaking: Supreme Court Majority Skeptical of Biden Student-Loan Forgiveness

Joe Biden’s order spending half a trillion dollars to forgive student debts without a Congressional appropriation finally got its day in court, despite frantic efforts by the administration to evade judicial review by repeatedly changing the rules to try to deprive anyone of standing to sue in federal court. The Supreme Court heard argument today on two challenges to the edict. The first session covered Biden v. Nebraska, which is the more direct of the two challenges because state entities are claiming losses from their roles as holders and servicers of loans, whereas the second set of challengers, in Department of Education v. Brown, are people left out of the program who claim that they were injured by the failure to follow proper administrative procedures.

The initial signs are ominous for the Biden Administration, whose only real chance of surviving these cases is to persuade the Court that none of these challengers have standing to sue. As to the question of the legality of the program, the post-9/11 HEROES Act — the theoretical basis for Biden’s emergency order — gives the secretary of education the power to "waive or modify any statutory or regulatory provision applicable to the student financial assistance programs" when "necessary in connection with a war or other military operation or national emergency." (Emphasis added). By contrast, various specific programs under the Higher Education Act statutorily authorize the secretary of education to “cancel” student loans. Missouri’s solicitor general, representing the challengers, noted, among other things, not only that “waive or modify” is a more limited grant of power but also that waiving or modifying provisions is narrower than waiving or modifying the existence of the loans themselves. Under that reading, the executive branch has the power to do things such as pause payments or waive requirements for qualifying for particular programs – for example, allowing a borrower to qualify for having spent a certain number of years as a teacher without those having been consecutive years if the teaching service was interrupted by a military emergency. It can prevent people from becoming worse off during an emergency. But it does not have the power to wipe the original pre-emergency debts off the books to satisfy pre-emergency political arguments for doing so.

Missouri’s argument found a receptive audience with Chief Justice John Roberts, whose vote would be essential if Biden wants to win this case. Roberts began the argument by citing an opinion by Justice Antonin Scalia, quipping that the statutory term “modify” can’t be read so broadly that one would say that the French Revolution modified the status of aristocrats sent to the guillotine. This case clearly irks Roberts and his sense that the “major questions” doctrine prevents presidents from ruling by executive edict and skipping procedural steps. He noted how this reminded him of the Court’s decision in Department of Homeland Security v. Regents of the University of California, which stopped the Trump administration from undoing an Obama-era unilateral executive edict. The fact that Biden was spending half a trillion dollars without asking Congress plainly alarms Roberts. In terms of the separation of powers issues, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson staked out the opposite pole — amusingly, given some of her anti-Trump decisions as a district judge, she expressed alarm that the federal government could be brought to a halt if states could just constantly file lawsuits to stop the executive from issuing fiats.

Justice Elena Kagan scoffed at “all this business about executive power,” arguing that Congress had given away such broad powers in the HEROES Act that it effectively let the horse out of the barn. Justice Brett Kavanaugh expressed the view that “waive” is, indeed, “an extremely broad word,” but as usual, did not totally show his cards when Missouri’s lawyer noted the additional problems with labeling this as just a waiver.

The major questions doctrine is a canon of statutory construction, one intended to protect the power of Congress from being consumed by creative lawyering in the executive branch. It holds that courts should be particularly skeptical about reading into vague statutory language an executive power to issue sweeping rules on an issue if that issue presents a major, contested public policy question. The solicitor general bet heavily on a highly implausible effort to argue that the major questions doctrine is supposed to limit the executive from making regulatory policy that affects individual liberty, but not to prevent the executive from making policy regarding federal benefits. The implicit assumption is that spending money can never harm anybody. It is rather amazing to make such an argument in a time of high inflation and rising debt, and there was no sign that even the liberal justices were buying the argument. If anything, given the history of the British monarchy’s battles with Parliament, the Framers of the Constitution would have been more alarmed at the prospect of the executive claiming sweeping authority to spend taxpayer money without any appropriation by the legislature. Even the solicitor general conceded that the case raises a “politically significant issue,” and she sounded as if she knew she would lose this argument and really just needed a face-saving way to not concede it.

Given the weakness of the administration’s position on the legality of the program and how unlikely it is that there are more than three votes for it, the main focus of both arguments was on standing to sue. The central issue is whether Missouri could sue over revenues to be lost by MOHELA, a Missouri state entity that owns some of the loans. Notably, the solicitor general conceded that MOHELA would have standing to sue. It would have been better if MOHELA had brought suit in its own name, given that it has the statutory “sue and be sued” power that allows it to litigate its own rights. The justices and the parties were left to speculate about why exactly MOHELA hadn’t sued – -Justice Jackson suggested that they might make the money back from effects of the program in other ways, while Justice Samuel Alito suggested that MOHELA’s “dependent relationship” with the federal student loan system made it fearful of going to court. Plainly, MOHELA was not eager to get involved directly, as illustrated by the fact that Missouri had to go through a state-level FOIA request to get information out of it. Missouri’s lawyer demurred, noting that Missouri rather than MOHELA filing suit was due to a “question of state politics.”

As a result, the Court was — as everyone agreed — on a certain amount of untrodden ground in deciding when a state can assert the rights of a state-created entity. Again, the solicitor general conceded that there was no case explicitly addressing the issue. There were analogies made to the rules for determining when a state entity is a state actor under the Fourteenth Amendment (MOHELA would likely meet that test, because it is still a public entity), or when it has state sovereign immunity (MOHELA would likely not, due to the sue-and-be-sued clause), but neither analogy decides the case unless the Court is willing to extend the analogy. Missouri argued that a creature of the state is a creature of the state even if it has a measure of financial independence, that the state retained a residual ownership interest in its assets, and most importantly, that the state should have the same powers as the federal government to sue on behalf of its own quasi-sovereign creations when they are injured. The solicitor general and the liberal justices stressed that there was a “wall of separation” by which the state is not on the hook for MOHELA’s liabilities and could disclaim them if it went belly-up.

The underlying embedded question is whether the Court would decide this issue as a federal question of Article III law or as really a state-law question of Missouri’s relationship with MOHELA under Missouri law. That subtext has been at issue in a number of the Court’s past decisions in hot-button cases, and where standing is concerned, the Court has typically not granted much deference to state law. In Hollingsworth v. Perry, for example, Roberts wrote that “standing in federal court is a question of federal law, not state law” in determining that the proponents of California Proposition 8 lacked Article III standing to defend California’s popularly-enacted ban on legally recognizing same-sex marriage, even after the California Supreme Court ruled that the proponents were authorized under state law to defend the proposition. The Court has been more lenient in cases last Term in allowing state officials to intervene to defend state laws, but those were not Article III standing cases. Of course, the most infamous example, which nobody would cite today for any purpose, was Dred Scott v. Sandford, in which the Court asserted that the question of whether black Americans were citizens with Article III standing to sue in federal court was a question of federal law rather than a matter of state law (there being a vigorous dispute, before the Fourteenth Amendment, on the question of whether there was a national definition of citizenship outside of the naturalization of immigrants, or whether U.S. citizenship depended upon being a citizen of a state.)

Among the conservative justices, Justice Amy Coney Barrett seemed most skeptical of Missouri’s right to represent MOHELA. But the focus of the other conservatives at argument on the merits suggests that the administration will have a hard time finding a fifth vote.

The sleeper case is the second one, but it involves a much more convoluted theory of standing: two student-loan debtors who were not covered by the Biden program argue that it should have gone through the mandatory “negotiated rulemaking” and notice-and-comment administrative procedures under the Higher Education Act and the Administrative Procedures Act. Of course, if the edict was authorized under the HEROES Act, it would be exempt from both of those requirements, so their argument requires the Court to decide that legal question. Under their theory, use of the HEROES Act deprived them of a fair administrative process in which to advocate for including them in the program. There is surprisingly strong caselaw supporting a broad reading of standing to assert procedural rights, and the solicitor general made an unpersuasive effort to distinguish their standing from that of people asserting equal protection violations, in which unfairness itself is an injury even if a victory in court might just strike down a program entirely. The liberal justices, arguing that it was speculative to think that Biden would try again under the HEA if his HEROES Act forgiveness was struck down, were not the only skeptics: justice Neil Gorsuch grumbled at using such an indirect attack to obtain a nationwide injunction against the program, and justice Clarence Thomas has argued in the past that limited standing should limit the sweep of the relief the Court orders.

In any event, Biden’s team is unlikely to get a ruling vindicating the legality of its actions or even a ruling saying that nobody can challenge them in court. The best outcome for the administration is to locate a fifth vote beyond the three liberals and possibly Barrett for the view that Missouri can’t represent MOHELA, coupled with peeling off a few of the conservatives to scale back standing to complain about administrative procedural violations.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

No comments: